How to Achieve a Better Portfolio View

The purpose of this article is to cover how you can produce accurate portfolio views (Cash and Position Management) at any point in time for both front, middle and back office use cases. This is done through an Investment Book of Record and we have a separate article that explains what an Investment Book of Record is as well as an entire guide on the topic of Portfolio Book of Record.

The first important parameter of transactions is the states they go through; we dive into that in our article on how IBOR enhances transaction lifecycle management. In the post you're reading now, we consider the second key parameter of transactions (and positions): time.

Temporality: As-is, as-of, and as-was portfolio views – Recognising that our view of transactions evolves over time

As a transaction progresses through its lifecycle, and its precision and certainty evolve, we learn more about it. We start with an expectation of the future – we can project (or guess) the times when its state will change, and we have an expectation of the terms of the transaction in each of those states.

Future portfolio views, such as cash forecasting

The future hasn’t happened yet, but it might be useful for us, especially in the front office, to see a projection of what likely future scenarios are. For example, assuming all your orders are filled at the last price, how does your settled cash look, per account, in 4 days from now? Is there a risk of an overdraft, or will there be buying power left untapped?

This scenario goes beyond payment of the assets and includes any fees incurred as a result and also new or changed dividends, coupon payments etc.

Throughout the lifecycle of a transaction, and as its states transition, the changes are recorded, and their impacts are applied to the projections. We refine our view of its likely future evolution continuously. Equally important, however, is the history of a transaction.

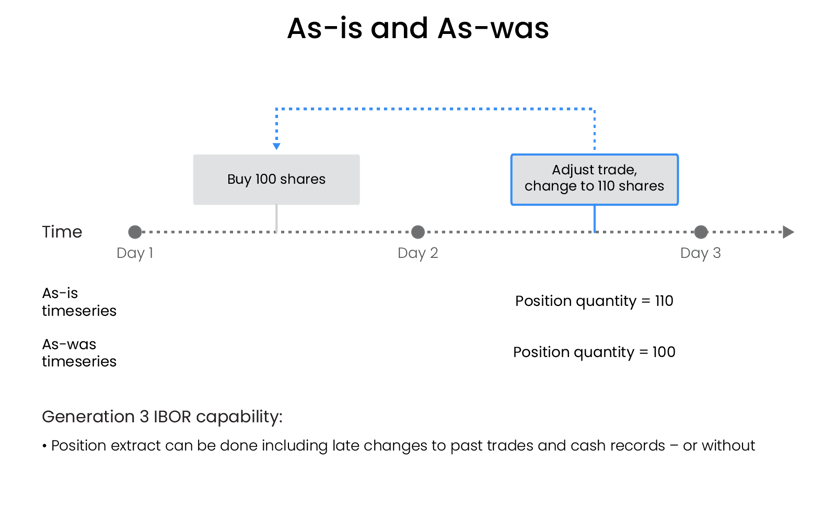

Historical portfolio views, including late adjustments

Once a transaction reaches the “Physical” state by settlement in the back office, our perspective becomes concrete. At this point, we have a full history of the transaction, and (subject to post-event reversals) we have no further expectations of future states or state transitions.

The final state of a transaction, where we know what happened, doesn’t devalue the previous views that we held; they were the best portfolio views that we could have had, at the time, based on the data available at the time.

The point is that there are two, rather than one, important dates in the assertion of a position view:

-

The effective date, when the asserted position data is valid.

-

The knowledge date, when we captured the transaction data from which the position view is constructed.

The effective date can be ahead of, the same as, or behind the knowledge date. If the effective date is ahead of the data point, then the position view is a forecast, based on transactions at the data point. If the dates are the same, then the position view is a snapshot, based on the most up-to-date transaction data at the time. If the position date is earlier than the knowledge date, then the position view is a reconstruction, based on retrospective data.

We are all more familiar than we might think with this distinction from individual use cases which are commonly supported in asset management systems. For example, a familiar instance of retrospection is a period-end accounting close, including late adjustments.

So, in this example, we may have an accounting position based on, say, data at month end. We then accommodate 7 days of late adjustments to get to a “definitive” month end position. What has happened here is:

-

On the last day of the month, we have a position with an effective date at the month end, with a knowledge date at the same point.

-

7 days later, we have a position with an effective date at the month end, but we now know that this should be different, as we need to incorporate our knowledge that some of the underlying transactions have changed through late adjustment.

Both of these position views are equally “correct”, depending on the use case of the positions.

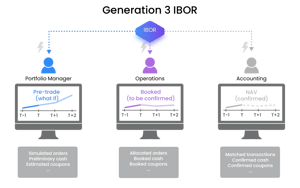

How an Investment Book of Record address bi-temporality to achieve any portfolio view

With a fully functional IBOR, this bi-temporality is not delivered as a bespoke treatment for one-off circumstances, but as a generic capability of the platform; every transaction state has a data point (i.e. its knowledge date) and an effective point (i.e. its effective date). Portfolio views derived from this transaction data can look forwards, be a snapshot, or look backwards accordingly.

It follows that the effective point for any position may be:

-

now, e.g. for an order that’s just been filled;

-

in the future, e.g. for a projected dividend; or

-

in the past, e.g. for a trade made last month

The data point may be:

-

Now, e.g. including all amendments to date. A concrete use case for this is a calculation of historical risk, where the Middle Office want to see the actual risk we had (not the risk we thought we had);

-

In the past, e.g. at the point, a NAV was set. A concrete use case for this is reporting of a NAV time series to investors. If we have later learnt that a transaction was incorrect, but the NAV is already struck, we want to base the time series on what we thought was right at that time; or

-

In the future, but only if we are using economic projection tools to forecast data!

With a live extract IBOR, any portfolio view is constructed on the best information available at the knowledge point about transactions at the effective point.

Our founder and CEO, Kristoffer Fürst, takes you through a full IBOR breakdown in the video above

IBOR Platform vs conventional approaches to position views

It’s common for position views in conventional asset management platforms to be constructed from transactions at different data points. Generally, including the most recent data that is available to the platform at the time the position view is created.

In conventional asset management architectures, the focus is normally on currently effective positions, based on recent transaction data. History is serviced from snapshots of portfolios stored in an archive or data warehouse. Forecasts are serviced separately from current positions, generally in treasury systems for cash positions, and through ‘what-if’ capabilities in portfolio management systems for future stock positions.

A properly constructed IBOR on the other hand will always construct positions from a consistent set of transactions at a consistent data point. In a fully functional IBOR, historic, current and future positions in both cash and assets are serviced from the same set of multi-state, bi-temporal transaction data.

Read more about Front-to-back vs IBOR Platforms.

Summary

Because of the capabilities a live extract IBOR include the management of the temporality of any transaction, asset managers can achieve enhanced portfolio views. This, in turn, provides greater clarity around the assets and cash, at any point in time, for both the Front, Middle and Back Office functions, ensuring portfolio views are accurate and consistent at all times.